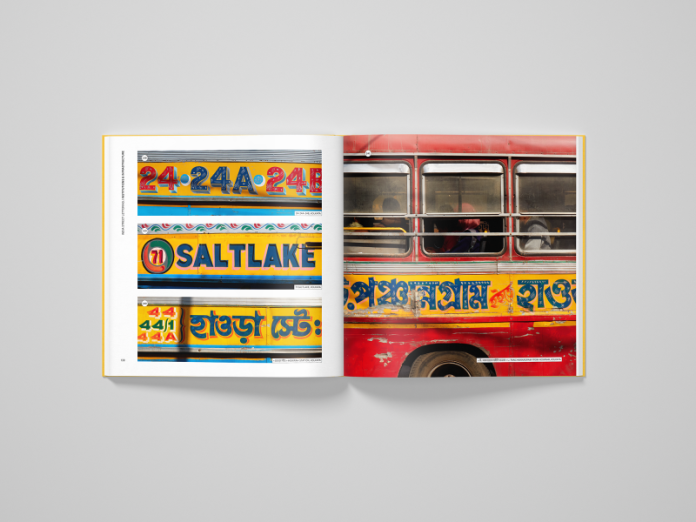

For designers used to working with digital typefaces and brand guidelines, India’s urban streets present an alternative typographic universe. It’s a frenzied, colourful kaleidoscope where painted signs compete with neon, mosaic sits alongside metal, and multiple scripts layer on top of one another in compositions that would never pass a corporate design review.

Yet as typeface designer and lettering artist Pooja Saxena has discovered through 15 years of documentation, this vast visual archive holds lessons that formal typography education often misses… yet it’s vanishing faster than anyone is recording it.

Her forthcoming book India Street Lettering, a 200-page hardcover releasing this December, represents the result of what began as a common designer’s obsession. “My beginnings were not very different from any other aspiring typeface designer, back when I was in university: who doesn’t get obsessed with all manners of found lettering?” she notes. But what started as a casual interest became something more serious after she completed her MA in Typeface Design at the University of Reading.

“India, of course, was a colony of the British until 1947,” she points out. “So vast repositories of archival material about Indian typography and print culture live in institutions in the UK, rather than in the regions where they belong. Ironic as that may sound, I had easier access to these resources in the UK compared to India.”

Building on this data, she began photographing, geotagging and annotating thousands of signs across more than a dozen Indian cities.

Watching signs disappear

The urgency of the project becomes clear when Pooja describes how she’s watched these historic signs vanish in real time. “I photographed the sign for Kolkata’s Elite cinema in late 2023, and by spring of next year, it was gone along with the entire building,” she recalls. “A few years earlier, the sign for Bengaluru’s iconic Parade Café saw the same fate.”

In Mumbai, an Art Deco sign on Queen’s Court was recently hidden by new construction. “All I have of that sign is an old, not-so-great photograph from 2017,” Pooja admits. “Every time something like this happens, the city loses a little more of its visual character.”

The replacement is often flex printing: digitally printed vinyl that can copy a painted sign’s look but lacks its material quality and evidence of craft. In Lucknow, Pooja watched as “most painted signs from Qaiserbagh Chowk were replaced by near-identical flex signs in a matter of months.” Digital printing means any shopkeeper can commission signage cheaply, but the signpainter’s distinctive hand disappears in the process.

What she documents

Pooja’s approach to building her archive is carefully considered. “I am wholly biased towards signs that are handcrafted or made using analogue techniques,” she explains. “So much so that I almost never photograph printed signs.”

More specifically, she looks for painted signs showing distinctive styles or exceptional skill, and tries to document multiple works by individual signpainters, “almost to create a visual monograph of their work”. But she’s also conscious of looking beyond paint. “I love signs in mosaic, for instance, or metal ones that mimic ribbon lettering and invite the play of light and shadow.”

As a typeface designer, she’s particularly drawn to “signs that feature unconventional construction of letterforms, or local interpretation of global design paradigms”—exactly the kind of vernacular innovation that rarely makes it into design history books.

Tracing the makers

Pooja didn’t have much trouble identifying the makers of the signs. “Many painters, for instance, actually sign their creations, complete with their contact details,” she says. “Signmakers across mediums—paint, wood, neon, etc.—are usually well-known in their neighbourhoods and communities; how else would they find work?”

Yet conducting interviews presented real challenges, with language proving the biggest barrier. During a recent trip to Kochi, she met Narendra, a sign painter working across the street from her hotel. “He spoke Malayalam, a language that is alien to me; I spoke Hindi, which was unfamiliar to him.” The interview only happened because “the shop owner encouraged him, and the receptionist at my hotel agreed to be our interpreter.”

How documentation feeds practice

Wondering whether this work has practical value? Pooja’s own practice shows its potential. She describes how “the form of Indic scripts that we usually end up seeing today is filtered through the conventions and constraints of Western printing and typesetting technologies.”

Many scripts were adapted to suit movable type, changing their appearance. “Handmade lettering on signage is an invaluable typographic resource,” she argues. “It contains the possibility of circumventing the functional limitations of mainstream printing and typesetting technologies, and offers ways of imagining letterforms that may be absent from canonical representations in type.”

And this isn’t just theory. In 2024, Pooja designed the identity for an exhibition called The Past Has a Home in the Future at Delhi’s Dhoomimal Gallery. The project required studying archival images of Connaught Place to trace the evolution of painted signs over the decades.

“Through this research, we were able to discern characteristic typographic styles from Connaught Place that captured the optimistic, industrial zeitgeist of the early to mid twentieth century,” she explains. “The resulting typeface family was a contemporary interpretation of years of creative expression from Connaught Place, something that I hope will be a thoughtful contribution to the continuum of art and design discourse emanating from the neighbourhood.”

It’s a great example of how documentation feeds back into contemporary practice, not through copying, but through understanding formal possibilities that commercial type production has historically excluded.

Why this matters

For designers outside India, India Street Lettering offers a case study in how local visual traditions resist and adapt global design norms. For those working with non-Latin scripts, it shows how letterforms evolve when freed from industrial constraints.

More broadly, for anyone concerned with preserving craft knowledge, it’s a reminder that some archives only exist if individuals commit to building them, sign by sign, before the digital printers arrive.

The book is available for pre-order at £14.98, with an ebook edition also planned. Given the pace at which Pooja’s subjects are disappearing, it may be documenting a typographic landscape that looks markedly different, even by its December release date.