New reports evidence the close collaboration between the Chinese Army and Public Security and opaque private companies.

by Massimo Introvigne

Bitter Winter recently reported on Salt Typhoon and UNC4841, based on a study by cybersecurity firm Silent Push exposing a Chinese cyber-espionage campaign that might have accessed the mobile phones of more than one million Americans and even hacked court-authorized wiretapping.

The Natto team of cyber-experts has recently offered new insights on the campaign. A report of October 23 explores the complexities of attributing cyber threat activity to Chinese state-linked groups, focusing on aliases like APT27, HAFNIUM, and Silk Typhoon. It highlights how cybersecurity firms and government agencies use varying naming conventions, often leading to confusion when multiple monikers refer to overlapping threat clusters. For instance, Microsoft rebranded HAFNIUM as Silk Typhoon in 2023, yet official documents still use older names depending on the context of the attack.

Drawing on indictments, sanctions, and leaked documents, Natto Thoughts maps connections between hackers and front companies, revealing a cyber ecosystem shaped by both state direction and freelance profiteering. The piece calls for greater clarity in naming conventions and deeper attention to the personal networks driving persistent cyber threats.

Previously, a September 25 report from the Natto Team offered a deeper look into the companies and structures behind the massive cyberhacking activities of Salt Typhoon, expanding our understanding of how China’s cyber apparatus operates.

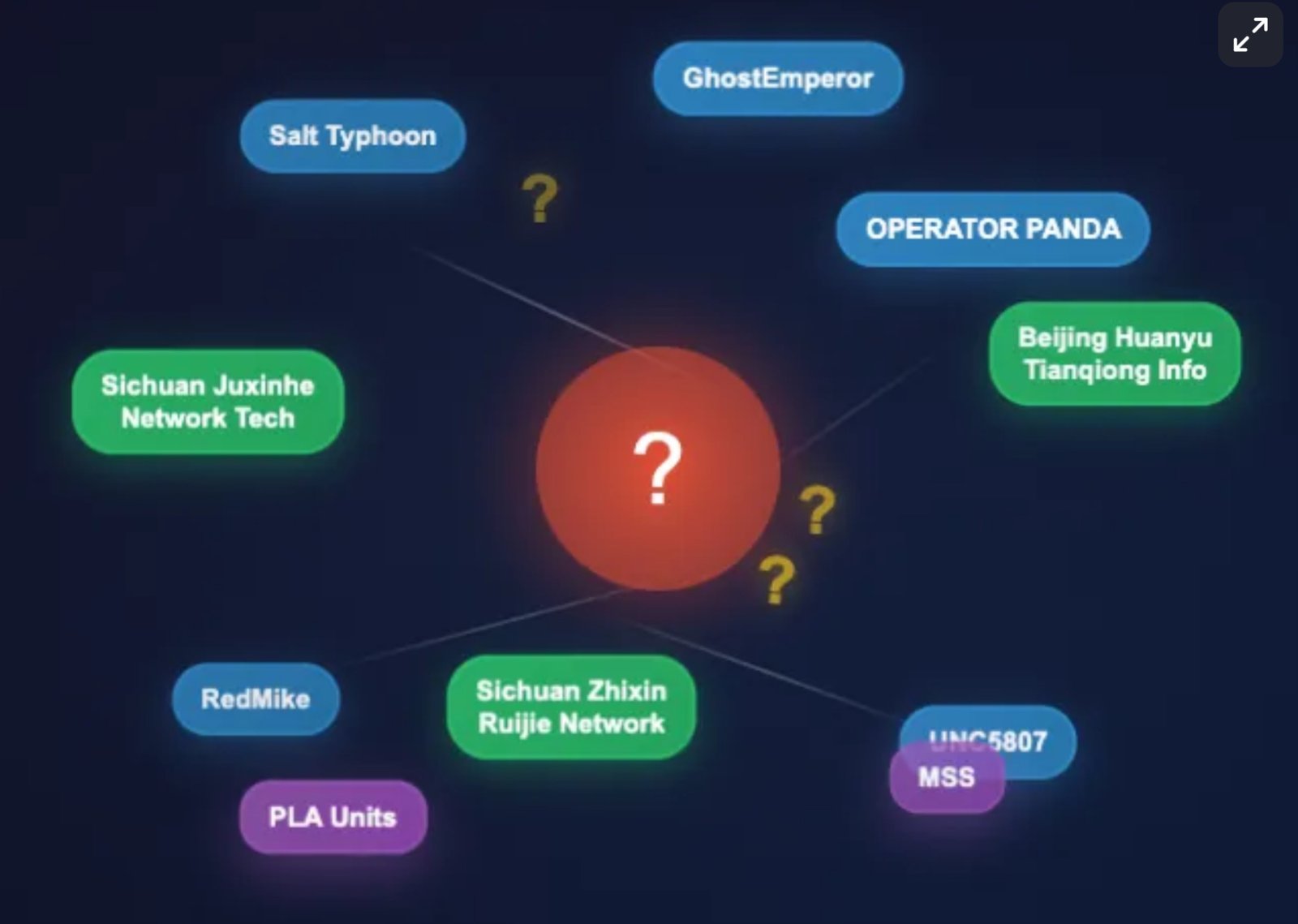

The Natto Team’s post builds on the Joint Cybersecurity Advisory by national agencies of thirteen countries issued on August 27, 2025, which named three Chinese companies with State Security connections—Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology, Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong Information Technology, and Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie Network Technology—as suppliers of products and services to Salt Typhoon and overlapping threat groups such as OPERATOR PANDA, RedMike, UNC5807, and GhostEmperor. Natto’s investigation focuses primarily on Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie, whose website had mysteriously vanished from public view. Thanks to Dakota Cary of SentinelOne, Natto located the company’s domain (0eye[.]com) and traced its ICP registration history, revealing that the site went dark when Salt Typhoon’s activities were publicly exposed.

This disappearance aligns with broader patterns: the company’s clientele includes government and military entities, and its website was likely hidden or deregistered to avoid scrutiny. Natto notes that Chinese law requires websites to display ICP and public security filings, and the absence of these records since May 2025 suggests deliberate concealment. Cached versions of the site show it was active from 2018 to mid-2022, but its removal coincides with increased global attention to Salt Typhoon’s operations.

The August advisory did not attribute the threat activity to any specific group. While cybersecurity firms often label actors as Salt Typhoon, OPERATOR PANDA, or GhostEmperor, the advisory instead used the broader term “APT [Advanced Persistent Threat] actors,” acknowledging the complexity and lack of consensus in attribution. “This means that uniformed personnel of China’s intelligence services may have conducted the threat activity directly using these companies’ products, or they could have hired these companies and directed them to perform services such as network intrusions. In either scenario, China’s intelligence services—such as units in the PLA [People’s Liberation Army] and MSS [Ministry of State Security]—could be the direct operators of the threat activities.” Natto views this as a constructive step, allowing agencies to focus on shared threat behaviors rather than disputed naming conventions.

The post also revisits past U.S. indictments—such as those against Chengdu 404 (APT41) and Boyusec (APT3)—to illustrate how Chinese companies have previously been linked to state-sponsored hacking. However, in this case, the advisory stopped short of naming the three companies as direct operators. Instead, it suggested that China’s intelligence services may have used these firms’ products or contracted their services for cyber intrusions.

In sum, Natto’s analysis reinforces Silent Push’s original reporting while adding technical depth and historical context. It paints a picture of a cyber-espionage ecosystem where private companies, military units, and intelligence agencies collaborate—sometimes opaquely—to conduct surveillance and intrusion campaigns. The threat is persistent, decentralized, and evolving. As Natto warns, China’s growing cybersecurity industry remains a key enabler of these operations.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.