Have you ever been bored? Have you ever been like, really bored, bored in the way where it feels like you’ve been removed from participating in the rest of the world, like time is moving differently for you than it’s moving for other people? How about depressed? Have you ever felt like everything you do is meaningless, like nothing ever changes, like every moment you’re living has happened before and will happen again, endlessly?

Need to Know

What is it? Time loop narrative RPG about mental health and Mars colonies. Or something.

Release date [Month XX, 20XX]

Expect to pay $XX/£XX [Remember: if the price is 49.99, round it up to 50.]

Developer [Who?]

Publisher [Who?]

Reviewed on [GPU, CPU, RAM]

Steam Deck Unknown

Link Official site

You play Eugene Harrow, a man fresh off a mental breakdown who’s been carted off to a motel in the middle of nowhere for some probably necessary but not very voluntary therapy and ends up stuck in a 47 minute time loop. This has the effect on his mental health that you might expect. As he explores the time he’s allotted, he discovers the secrets of the loop, learns about the community he’s found himself in, and figures out how to make it out in one piece.

At least, that’s the pitch.

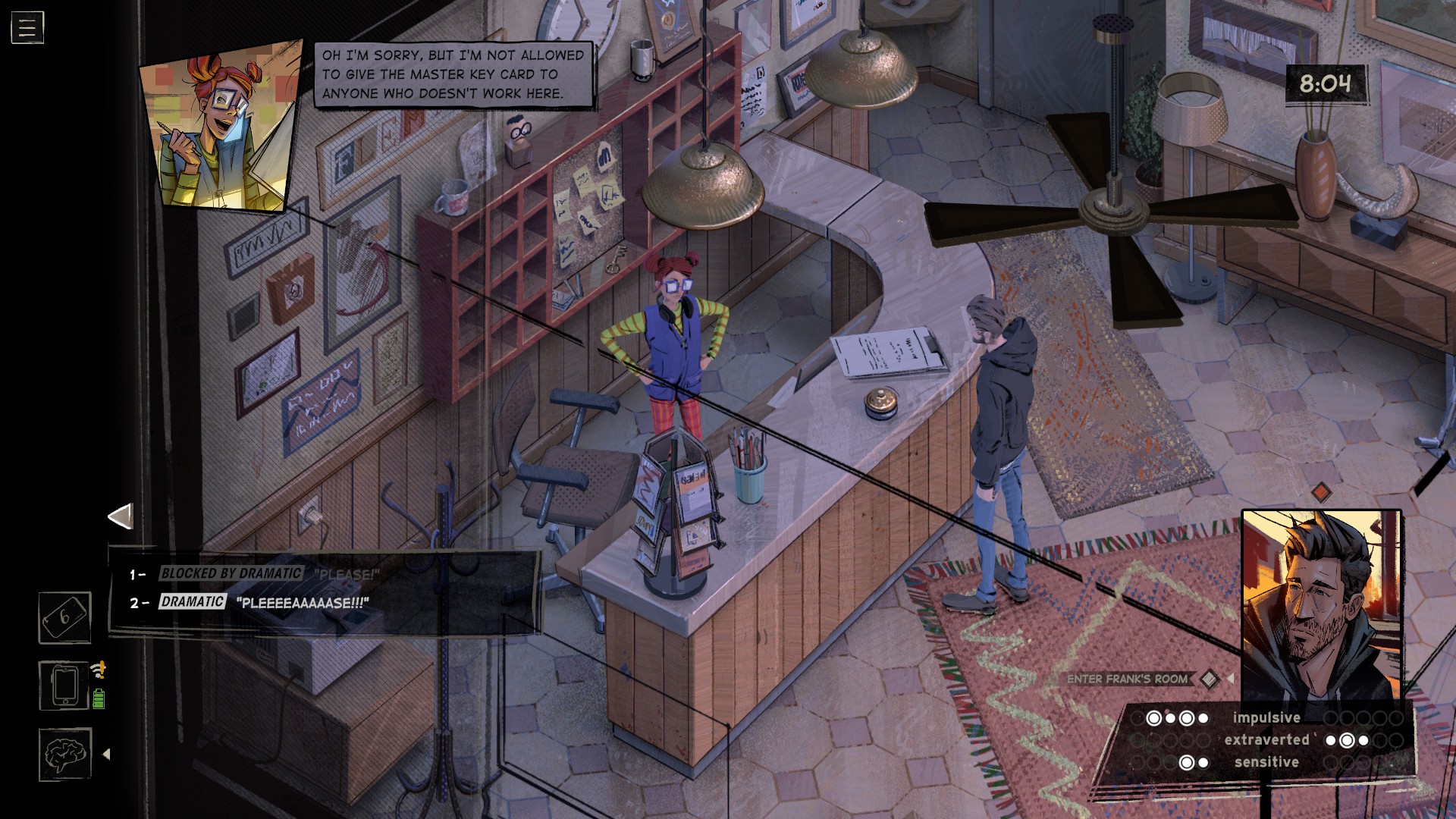

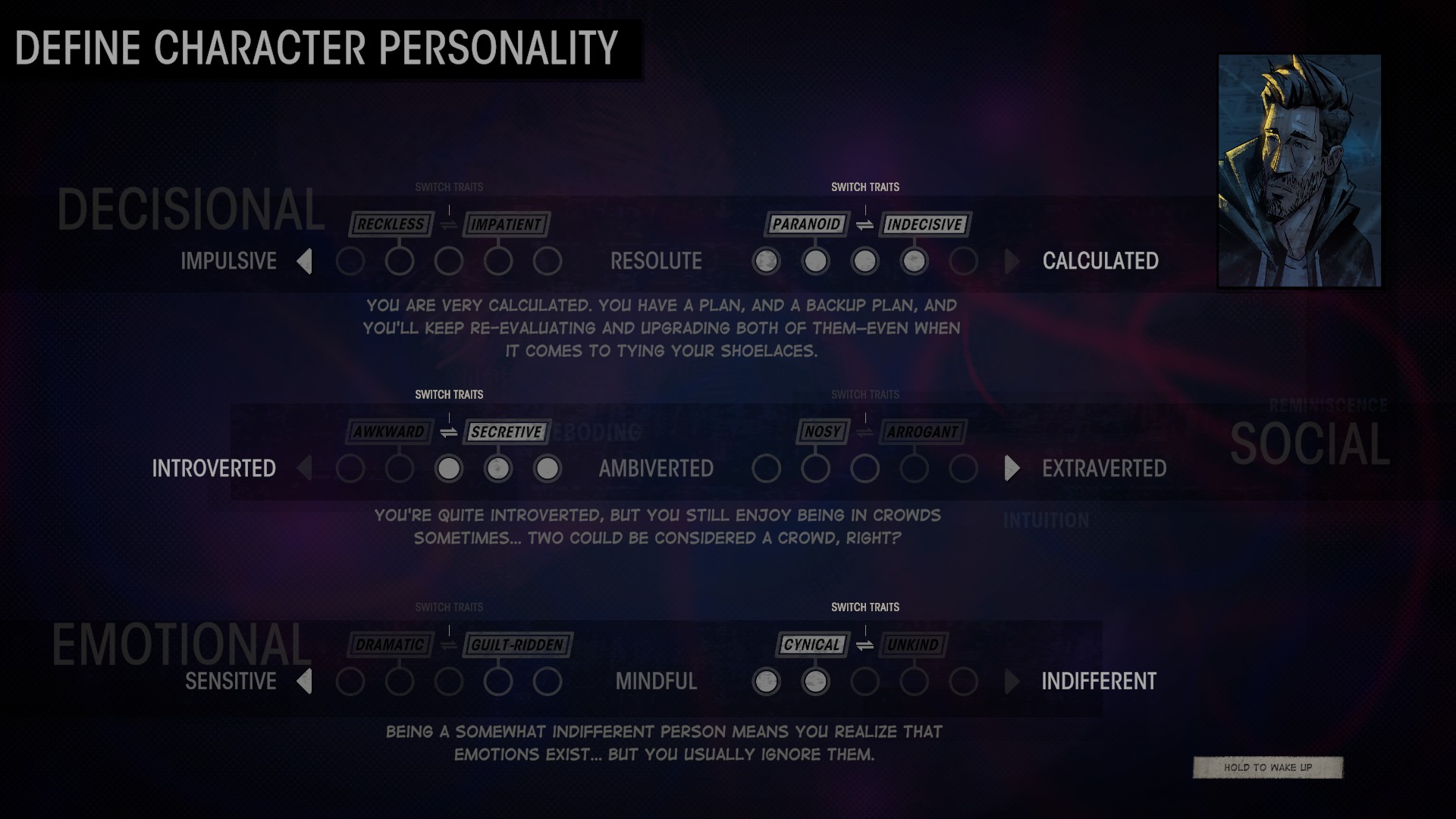

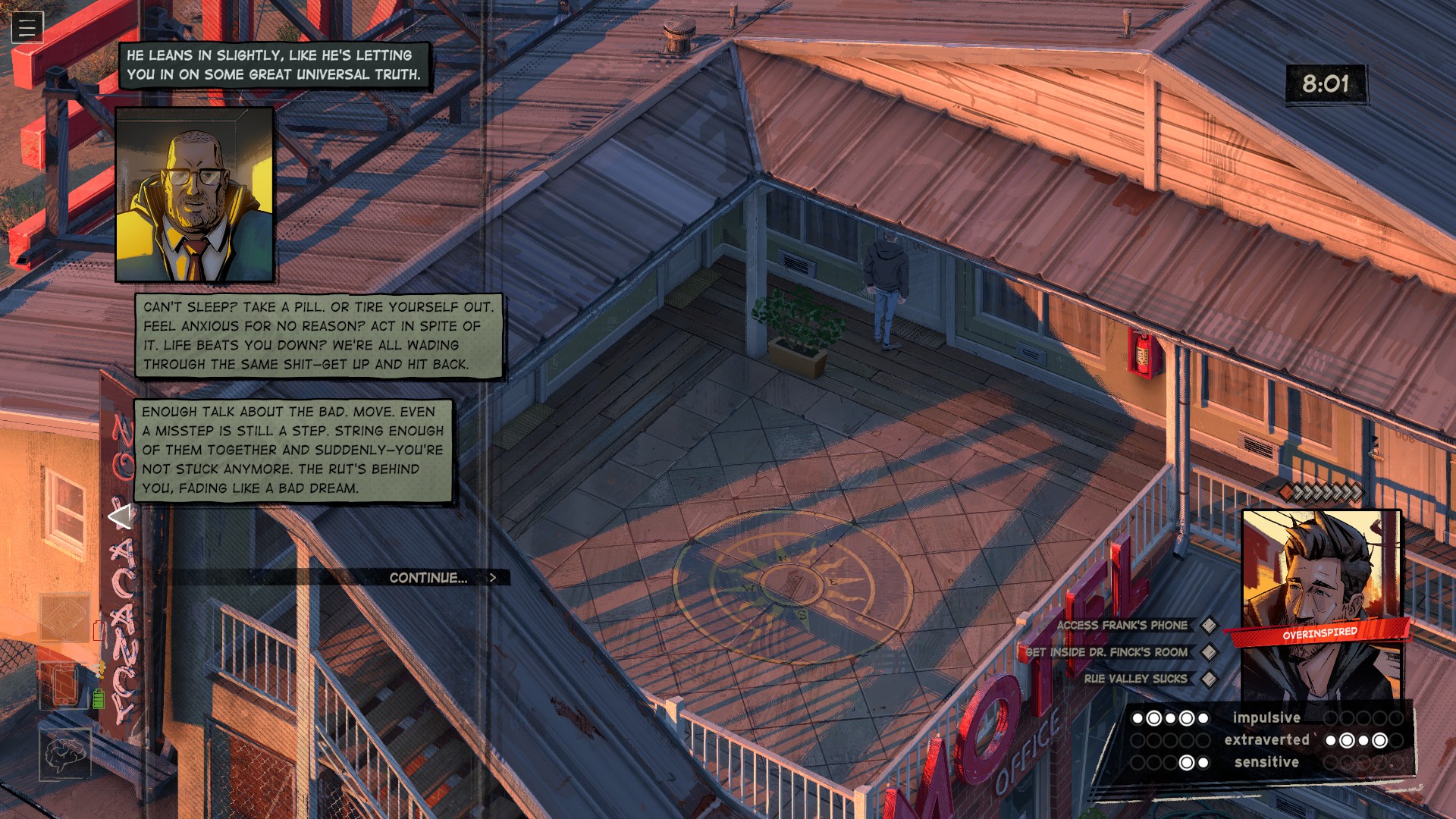

Rue Valley is what I guess we have to call a Disco Elysium-like: isometric maps, stylized art, no combat, conversation-centric, with a hyper-internal protagonist whose personal monologue forms the bulk of the text. The conversation UI is on the left instead of the right, though, so we’ve shaken up the format somewhat. Character creation involves sliders between introverted and extroverted, impulsive and calculated, and sensitive and indifferent, with promises that it will be Eugene’s reactive and customizable personality that makes your journey through the 47 minutes of his life unique.

This doesn’t really happen. Eugene’s personality comes out in interjections and exclamations (if you’re extroverted) or grayed-out dialogue options (if you’re introverted), none of which radically alter the outcome of conversations or your ability to complete quests. In fact, very little you do seems to alter any outcome of anything. It becomes clear after playing for a while (and after I restarted because my introverted, suspicious build was just too boring) that, despite the different ways you can build Eugene’s character, he’s really only going in one direction.

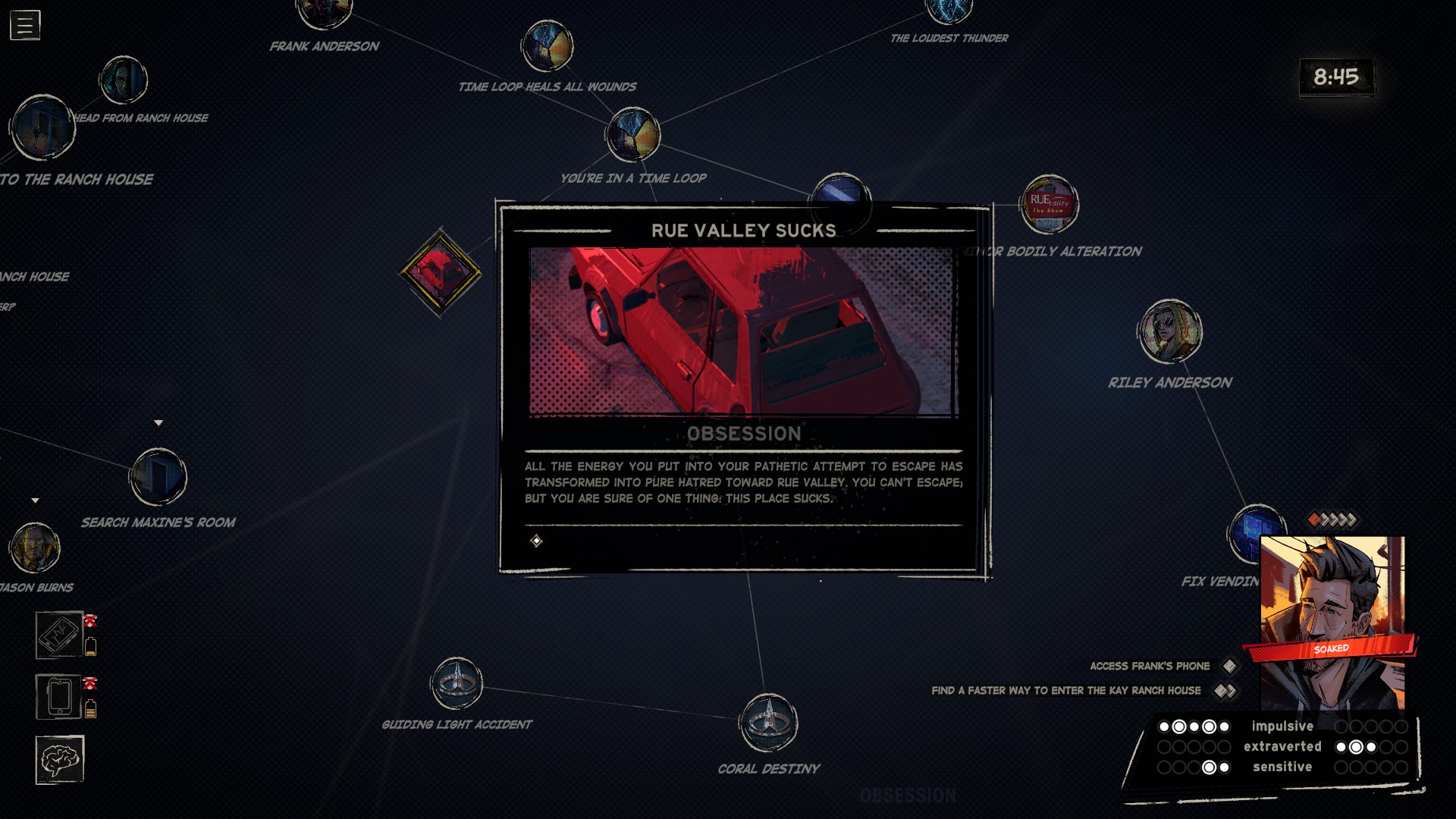

It’s a shame, because there’s the basis of an interesting game here. The mental health allegory is well-served by the format of the action economy: inspiration points can be used to activate “intentions” (read: quests), and as Eugene’s mental health improves he also acquires willpower, which is essentially a permanent inspiration point that can be reused after an intention is completed. Nice conceptually, but in practice pretty pointless, as there’s enough inspiration around to do whatever you want as long as you’re patient enough.

It does, though, lead to frustrating instances where Eugene has acquired information but can’t act on it until he has enough inspiration to activate the related intention. I have to loop six times to figure out I’m not in a reality show but I can’t take a minute to break into someone’s car? Sure.

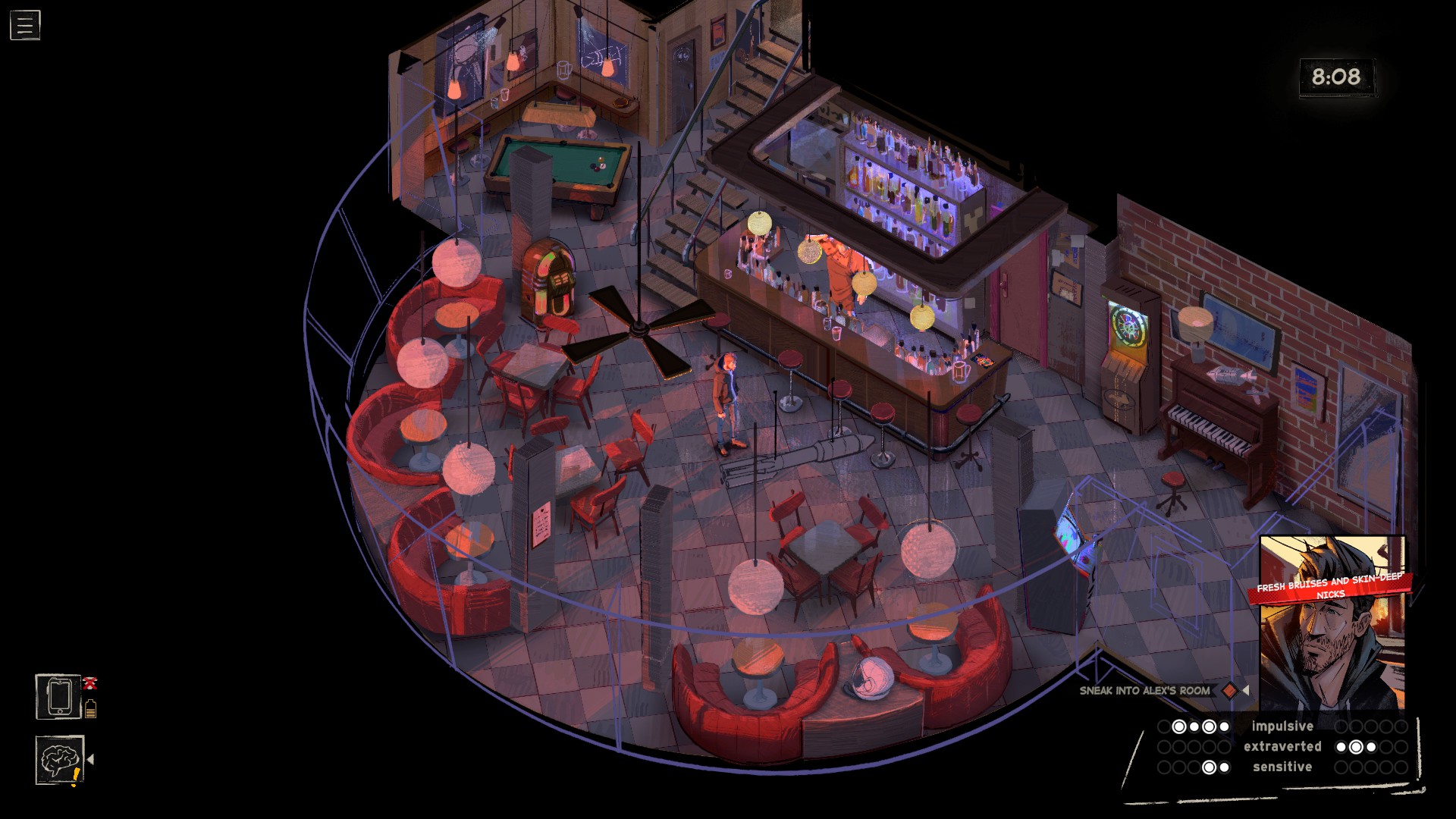

It feels like a time-wasting mechanic, of which there are many. Don’t get me started on the distance between locations, which serves only to carve off chunks of time from your already limited resources, ensuring that if you want to get anything done at multiple locations on the map you’ll be subject to a deadening circle of loop-end triggers, morning conversations, and overlong driving cutscenes. (The game recognizes this in more than one quest and hits a fast-forward button, allowing you to just watch the dull, repetitive montage of Eugene waking up, dashing out of the motel, going to a location, and trying to do whatever it is he needs to do instead of pressing the buttons yourself.) If you’ve done what you want to do for this loop, you’ve got to fuck around on your phone until the loop ends, which would feel like a waste of precious minutes if there was any indication you had anything better to do with them.

The bland irritation of repetition, a core tenet of any time loop game, has so little to interrupt it in Rue Valley that it loses all meaning. It did not feel like Eugene was trudging through a grueling experience to which I was party; it felt like a game developer was wasting my time.

The unconvincing mechanical structure of the game is unfortunately not helped by its story. There is a lot going on in the background of Eugene’s 47 minutes, which is great because Eugene is new to town, doesn’t know any of these people, and has no stake whatsoever in the goings-on of their lives. The result is that he wanders around, asks people questions, learns keywords, loops, and wanders around to ask people more questions about more keywords. Occasionally he gets a wi-fi signal and can search the internet for said keywords, which leads to more infodumps.

There’s a looming corporation with a financial interest in the town and aspirational Mars colonies; there’s the lingering damage of burnt-out family feuds and political dynasties; there’s a mysterious, loop-resistant figure Eugene spots on his first night who is significantly more interesting before you learn anything about him. I retained extremely little of all this history. There’s no reason to. You never have to actually learn anything in order to make your way through the world. You just have to figure out what the one option you’re presented with is, and go do it.

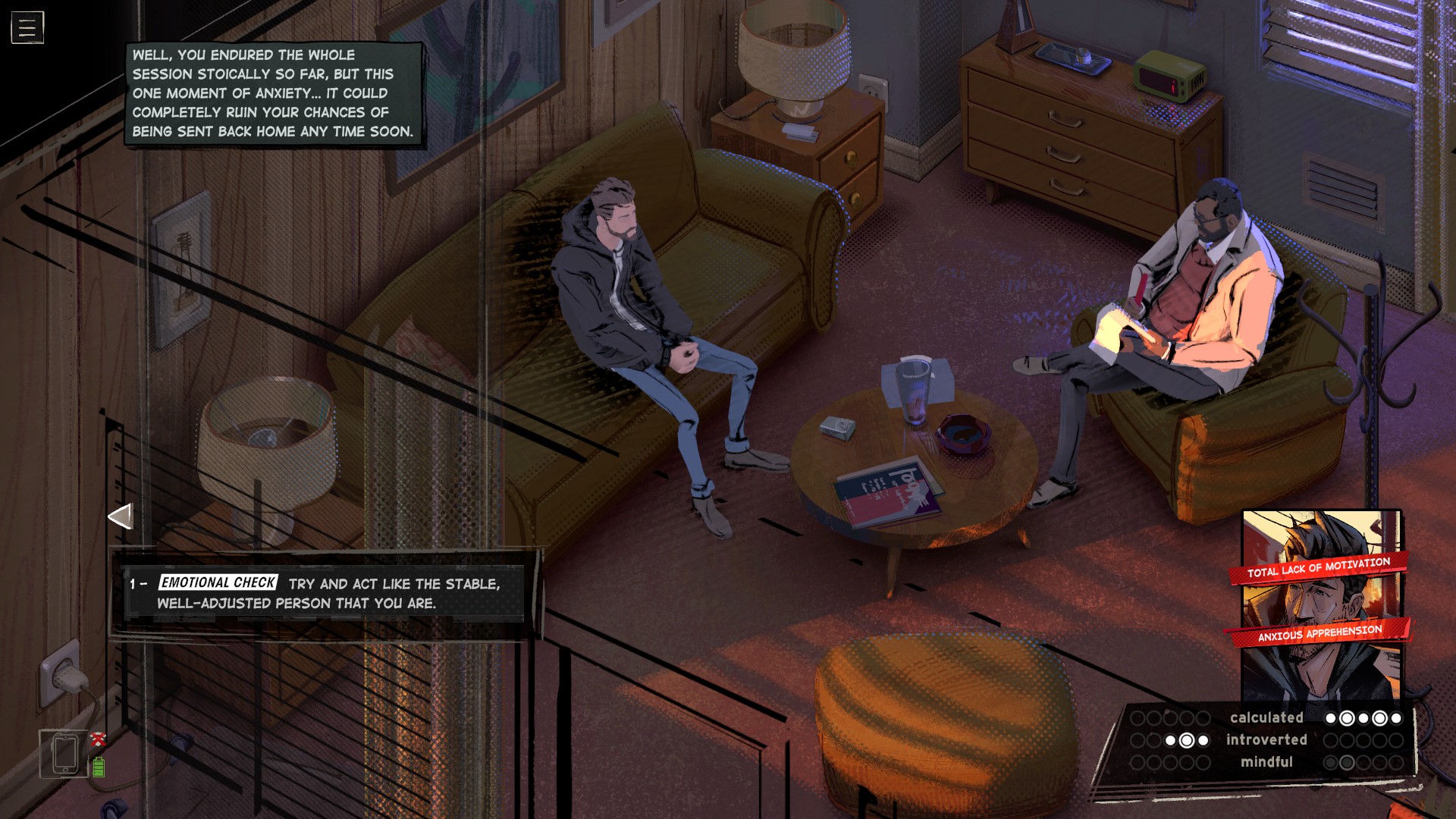

There are occasional moments of reprieve from this monotony. The beginning sequence, in which Eugene wakes up with a “total lack of motivation” status effect and wanders around the motel for the first time, apathetically refusing to react to the new world around him, was a bleakly funny and extremely accurate illustration of what it feels like to be that depressed. A sidequest that involves driving as far as you can as fast as you can in an effort to break the loop by force ends in a way that’s pleasantly sickening. When Eugene realizes the only way to get past a certain character is to kill him he swings between moral dilemma and emotional whiplash, the aftermath of which is the game’s most interesting exploration of the psychology of the time loop.

Unfortunately these moments are few and far between.

I struggle to articulate why Rue Valley, which on its face is well-constructed and pretty, doesn’t really work. What I keep coming back to is that it doesn’t commit to its own concept. With the theoretically infinite depth of the time loop, there should be ample room in these 47 minutes for small-town drama, sci-fi conceits, and various iterations of Eugene’s personal turmoil. Instead, the loop becomes an excuse for its own shallowness.

It borrows the trappings of Disco Elysium without understanding why Disco Elysium’s verbosity, internalization, and limited mechanics worked. It hits on an extremely effective metaphor—time loop as manifestation of depression, surreal happenings as literalization of mental state—and then fails to do anything with it. It could have theoretically been an interesting commentary on isolation and stagnancy, on mental health, on circular loneliness and the commitment it takes to work through it.

Instead, it’s a game where nothing really happens and you don’t do much. I can’t blame Eugene for his total lack of motivation.