By Michael Ullman

All three records were recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studio. The sound is what one would expect from Van Gelder, clear, bright and close: these LPs were made with care at every stage. I recommend all three.

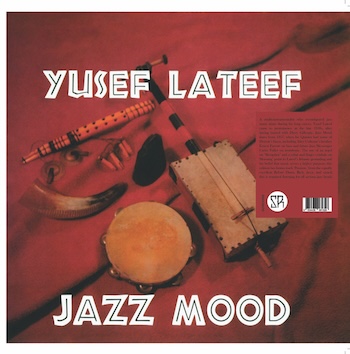

Yusef Lateef, Jazz Mood (Savoy/ Craft LP) April 9, 1957

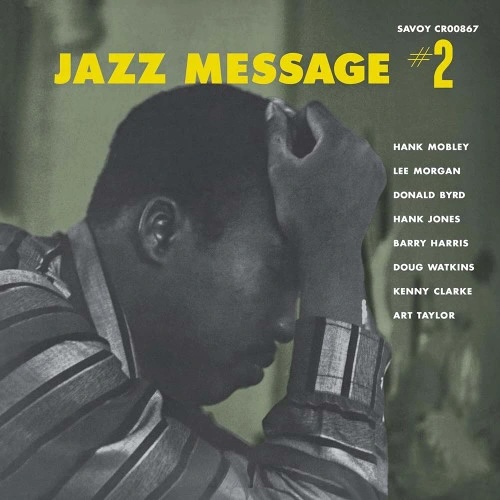

Hank Mobley, Jazz Message #2 (Savoy/ Craft LP) July 23, 1956

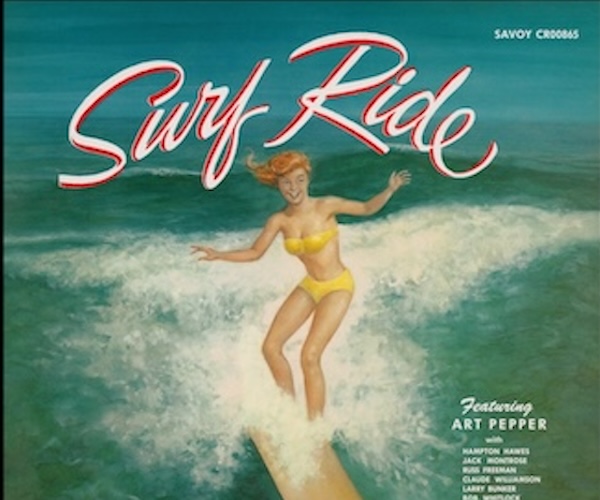

Art Pepper, Surf Ride (Savoy/ Craft LP), 1952-54, released in 1956

Savoy Records was founded in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky, whose previous career was mostly in radio. He also owned what turned out to be an influential jazz record store in Newark, New Jersey: the Radio Record Shop. Selling records must have given him the idea of making his own. He struck gold almost immediately. Lubinsky’s musicians may not have been happy with their business arrangements with the notoriously stingy producer, but he knew what he was doing in music.

Savoy Records was founded in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky, whose previous career was mostly in radio. He also owned what turned out to be an influential jazz record store in Newark, New Jersey: the Radio Record Shop. Selling records must have given him the idea of making his own. He struck gold almost immediately. Lubinsky’s musicians may not have been happy with their business arrangements with the notoriously stingy producer, but he knew what he was doing in music.

Lubinsky also had a worthy accomplice. His music director in the early years was high school dropout Teddy Reig, who has been described by Bob Porter ignobly as “a fat kid who could fight.” Reig was a ne’er do well, a self-described “jazz hustler” who, like Lubinsky, found his way into the music business by hook and by crook. Musically he was prescient. An adventurous and perceptive producer, he made Savoy Records (with only Dial Records as a rival) into the premiere bebop label. On November 26, 1945, for instance, he recorded the “Charlie Parker’s Reboppers” session. In one day, they waxed the classic “Now’s the Time” and “Billie’s Bounce”, and the famous, almost themeless, “Ko-Ko”. Reig was taking a chance, really a series of chances, with this new music, which many listeners would find obscure. A month earlier, he had recorded Dexter Gordon playing “Blow Mister Dexter” and Kai Winding leading the session that made “Grab Your Axe, Max.” Before 1946 was out, he had brought Fats Navarro, J.J. Johnson, Sonny Stitt, and Lockjaw Davis into various studios. All would become revered stars in jazz.

Reig moved on but, its reputation made by the bebop years, Savoy Records continued recording jazz and other music, including gospel. (The label is now owned by Concord.) The three beautifully reproduced LPs listed here were made between 1952 (Art Pepper) and 1957 (Yusef Lateef). The Hank Mobley session is from 1956. They were produced by Ozzie Cadena, another jazz hustler to whom we owe a huge debt. He too sidled his way into the none too profitable jazz record business, working at Lubinsky’s Newark’s Radio Record Shop before becoming, in the mid-’50s, a producer. After that, his name seemed to be everywhere.

The three Savoy albums listed here have been reissued by Craft Records on heavy-weight vinyl. The surfaces are satisfyingly quiet. I love the ’50s covers brightly reproduced here. Art Pepper’s Surf Ride, which was assembled from three sessions in 1952, features such West Coast stars as Hampton Hawes. Pepper was located in L.A., which must have seemed a rather exotic place from Savoy’s Newark. Hence the surfing references. The cover reproduces a painting by Harvey Ragsdale of a young bikini clad redhead woman with a manically happy, though none too well drawn, look on her face as she surfs. Californians must surf, right? If you knew Art Pepper, you’d realize he’d be the last person you’d find on a surfboard, maybe even on a beach. The only references to surfing, though, in the actual selections is Pepper’s original blues “Surf Ride”. (Five numbers are named after spices, presumably because of Pepper.)

The LP opens with Lester Young’s “Tickle Toe“, the first of four numbers that features a huge gathering of West Coast talent, including pianist Russ Freeman, with Bob Whitlock on bass and Bobby White on drums. The most famous of the compositions played here is “Straight Life”, which later became the title of Art Pepper’s very frank autobiography. The rendition here is almost manically fast, with Pepper and tenor saxophonist Jack Montrose racing through the melody in unison. I prefer the jaunty mid-tempo piece “Brown Gold”. Everywhere, though, Pepper’s playing is clean and controlled: he was a virtuoso bebopper, lyrical at any tempo.

The LP opens with Lester Young’s “Tickle Toe“, the first of four numbers that features a huge gathering of West Coast talent, including pianist Russ Freeman, with Bob Whitlock on bass and Bobby White on drums. The most famous of the compositions played here is “Straight Life”, which later became the title of Art Pepper’s very frank autobiography. The rendition here is almost manically fast, with Pepper and tenor saxophonist Jack Montrose racing through the melody in unison. I prefer the jaunty mid-tempo piece “Brown Gold”. Everywhere, though, Pepper’s playing is clean and controlled: he was a virtuoso bebopper, lyrical at any tempo.

Hank Mobley was once described by jazz critic Leonard Feather as the middleweight champion of the tenor sax: he wasn’t Sonny Rollins or John Coltrane. He turned out to be influential in his own way. In 1956, he made The Jazz Message of Hank Mobley, reissued as The Birth of Hard Bop and then by Arista in 1971 under the title Hard Bop. Hard bop was a ’50s return to a heavy blues orientation and a sometimes funky beat. (Its heroes included Horace Silver and Art Blakey.) Mobley was a key part of the movement. The Jazz Message No. 2 is a hip blues record, hard bop at its finest. Its message is five blues made at two sessions by all-start quintets: the first side has Lee Morgan, Hank Jones, Doug Watkins, and Art Taylor. It opens with “Thad’s Blues”. The record is an important link in jazz history: it’s good to have it available again.

Recorded in a single session on April 9, 1957, Jazz Mood was Yusef Lateef’s debut as a leader. He was 27 and living in Detroit, then a hotbed of jazz. Lateef, born William Emanuel Huddleston, adopted his Muslim name after his conversion. He wasn’t new to the music: as early as 1949 he had toured with Dizzy Gillespie. Jazz Mood features Curtis Fuller on trombone and tambourine, Hugh Lawson, piano, Ernie Farrow on bass and rebab, Louis Hayes and Doug Watkins on percussion. Lateef was a multi-instrumentalist, a tenor saxophonist who also played flute, and oboe. He became renowned for blending jazz with Eastern and world music elements, as heard especially on his album Blues for the Orient.

Recorded in a single session on April 9, 1957, Jazz Mood was Yusef Lateef’s debut as a leader. He was 27 and living in Detroit, then a hotbed of jazz. Lateef, born William Emanuel Huddleston, adopted his Muslim name after his conversion. He wasn’t new to the music: as early as 1949 he had toured with Dizzy Gillespie. Jazz Mood features Curtis Fuller on trombone and tambourine, Hugh Lawson, piano, Ernie Farrow on bass and rebab, Louis Hayes and Doug Watkins on percussion. Lateef was a multi-instrumentalist, a tenor saxophonist who also played flute, and oboe. He became renowned for blending jazz with Eastern and world music elements, as heard especially on his album Blues for the Orient.

The most original-sounding number on Jazz Mood, “Morning” begins with a rhythmic figure played on a string instrument, the rabat, backed by tambourine. It’s not the usual hard bop setting but, as he soon proves, Lateef could be a wonderfully expressive blues player. His solo on “Morning” is played over some sparsely offered comping on piano and the initial percussion. The session opens with “Metaphor”. It’s not clear to me what Lateef meant by the title: the song opens with a plucked bass note that serves as a drone. Lateef opens on the argol, soon switching to the flute. He and trombonist Fuller state the melody together. Eventually, the rhythm section starts playing in four and Lateef just wails the blues on flute. Jazz Mood centers on Lateef’s bold, touching blues playing.

All three records were recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s famous studio. The sound is what one would expect from Van Gelder, clear, bright and close: these LPs were made with care at every stage. I recommend all three.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 30 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He is emeritus at Tufts University where he taught mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department.