This is WESA Arts, a weekly newsletter by Bill O’Driscoll providing in-depth reporting about the Pittsburgh area art scene. Sign up here to get it every Wednesday afternoon.

In these days of ubiquitous digital media, one function of the Carnegie Museum of Art exhibit “Black Photojournalism” is to revisit a time when images were both harder to make and scarcer to consume.

The show covers the decades between World War II and about 1984 — from the “double V” campaign to Jesse Jackson’s first presidential run. That period of course includes the height of the civil-rights movement. But Black life in America was still both underrepresented and poorly served by white-owned media, partly because of how few Black journalists such outlets employed. (And so things to a troubling degree remain today.)

It was also when Pittsburgh’s own Charles “Teenie” Harris was in his long heyday at the Pittsburgh Courier, and he and his camera were out daily documenting seemingly every civic gathering, jazz gig, sandlot ballgame and celebrity appearance one could imagine.

But Harris, though uniquely prolific and accomplished in Pittsburgh, was hardly alone in his work. Drawing on multiple archives, “Black Photojournalism” includes some 200 images by nearly 60 photographers, from Gordon Parks and Austin Hansen in New York and Bob Black in Chicago to Bob Douglas in Detroit, David Johnson in San Francisco and John W. Mosley in Philadelphia. Chronologically later sections of the exhibit highlight more women photographers, including Coreen Simpson and Ming Smith. Most of the photos, of course, are black-and-white.

The show honors a similar array of Black-owned publications, from the Courier to the New York Amsterdam News, the Los Angeles Sentinel and the Baltimore Afro-American. At its peak, the Courier was nationally distributed, with a circulation of 357,000. The Chicago Defender printed 200,000 copies of each issue. Also represented here are the pioneering nationally circulated Black monthlies Ebony (founded in 1945) and Jet (1951).

The range of images captured is wide, too. There’s everything you’d expect from a mid-century newspaper: protest marches, sports, musicians on the bandstand, politicians on the podium. But co-organizers Dan Leers and Charlene Foggie-Barnett have also incorporated stuff you wouldn’t find in your daily (or weekly) serving of newsprint, from artful street photography to the occasional nude. “Black Photojournalism” even samples fashion photography and 1970s ads for Carlton cigarettes.

Strictly, ads aren’t “journalism.” But some photojournalists also shot ads. And certainly without a strong Black-owned press, most of what’s depicted in these photos — everyday scenes of Black joy, resilience and community — would have been lost to history.

Witness Harris’ photos of beaming fans dressed up for a ballgame at Forbes Field, and of the groundbreaking Billy Eckstine Orchestra in action (with the Pittsburgh-born Mr. B on trombone and Sarah Vaughn looking on). Or E.J. Doran’s circa 1940 shot of a centenarian signing up for his NAACP membership in Bridgeport, Conn.

Mosley captured future Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah at Philadelphia’s Pyramid Club in the 1940s, and Albert Einstein visiting Pennsylvania HBCU Lincoln College in 1946.

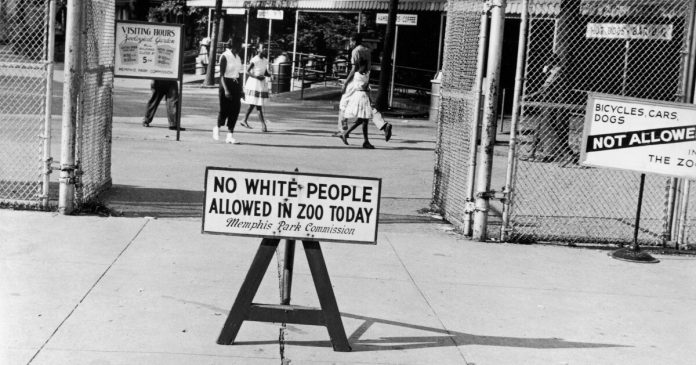

In John F. Glanton’s striking “Pool Match,” from the 1940s, the hats alone summon an era; so does the Memphis Park Commission sign “No Whites Allowed in Zoo Today” in a 1953 photo by Ernest C. Williams.

Also highlighted are images from Moneta Sleet Jr., a friend of Martin Luther King Jr. who documented the great man not only thundering from the lectern, but also at home, playing with his kids. Sleet was the first Black photographer to win a Pulitzer Prize for his image of Coretta Scott King at her husband’s funeral, also included here.

The show documents the gradual rise of a more subjective style of documentary photography. One of the exhibition’s best is Roy DeCarava’s haunting “Graduation” (1949), depicting a young woman in a white gown and long white gloves, walking in a dramatic slash of sunlight between the shadows of tall buildings, and past piles of rubbish. (DeCarava became the first Black person to receive a Guggenheim fellowship.) Street photography by Ming Smith is in a similar vein.

“Black Journalism” includes, under glass, vintage copies of key publications, including 1950s issues of Jet. And look closely at a yellowed 1963 copy of the Cincinnati Herald for a publicity photo and brief story about the local debut of that brand-new singing sensation, Little Stevie Wonder.

The exhibit also offers a big newsprint handout that reprints nearly 40 of the show’s images; a touchable display of Liz Johnson Arthur’s fabric-art books incorporating images from the show; and a companion podcast series.

“Black Photojournalism” continues through Jan. 19.