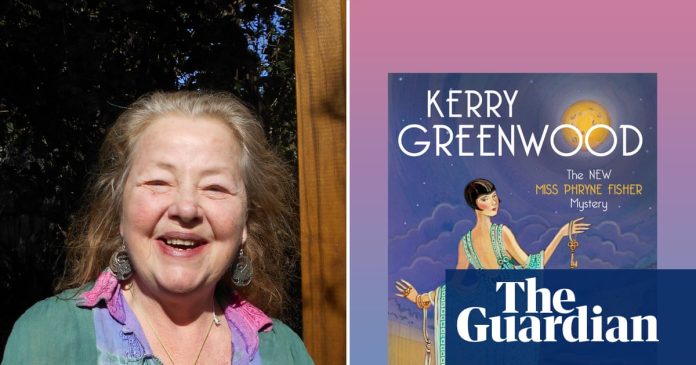

What a bittersweet pleasure it is to return to the Honourable Miss Phryne Fisher and 1930s Bendigo in the 23rd novel in Kerry Greenwood’s historical mystery series – and the final instalment, after Greenwood’s death in March.

The amateur detective Phryne Fisher is back to solve a tricky ecclesiastical mystery in her characteristically glamorous style. She is summoned to Bendigo to watch her old friend Lionel become the colony’s new bishop. But country towns “incubate secrets like greenhouse tomatoes” and Phryne can sense trouble.

When “the late, not terribly lamented” Deacon Holloway is stabbed to death in front of a full congregation, Phryne and friends are thrust into a locked-room mystery, where she must figure out who the unknown killer is – and uncover the “dark and dreadful” secret that made Holloway a target.

As is usual for Greenwood’s Phryne Fisher books, Murder in the Cathedral plays out as a self-contained mystery with a familiar cast of characters. It’s a chance to farewell series regulars Dorothy Williams and her soon-to-be-husband Constable Hugh Collins; Phryne’s wards Jane, Ruth and Tinker; her housekeepers Mr and Mrs Butler; and “red-ragger” mates Bert and Cec.

The household is joined by other familiar faces: Det Insp Mick Kelly and niece Colleen (from Death in Daylesford), as well as glimpses of Peony and Carnation (from Murder in Williamstown) and Phryne’s lover, Lin Chung (a favourite since Ruddy Gore). Like Sherlock Holmes (with whom Phryne famously shares an address), this instalment even comes with a Watson: Bendigo constable Matthew Watson, who joins her crime-solving team.

Fans of the series over the last 36 years will relish the warmth, wit and nostalgia, and the chance to spend another few hours in Phryne’s erudite company (I learned several new words). I was also grateful for the many reminders of what made Australia’s “sexy Miss Marple” so popular: Phryne is a strong, clever and fiercely independent protagonist, an unusual aristocrat as “rich as King Midas” who “dresses like a fashion model”. She also knows humility from being “born among the common people and translated to the upper crust later in life” – so we don’t begrudge the 30-year-old heroine her sensual and luxurious lifestyle. Phryne enjoys her men but doesn’t defer to them, and instead creates community through her ever-expanding found family. She is a fierce advocate, a kind benefactor, and a radically forward-thinker who blasts through social norms with ideals a century ahead of her time.

Each book is a love letter to Melbourne and Victoria, where Greenwood lived and wrote Phryne’s adventures – which span 23 novels, a short story collection, an ABC TV series (Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries), a spin-off about her niece Peregrine (Ms Fisher’s Modern Murder Mysteries), a video game (Miss Fisher and the Deathly Maze), and a feature film (Miss Fisher and the Crypt of Tears). These are just a fraction of Greenwood’s oeuvre, which included nearly 60 books after a career in legal aid. The stakes are high for this much-anticipated finale, and critique is difficult when so many are still grieving her loss. So, we can forgive if Murder in the Cathedral is not quite as polished as her previous books, given Greenwood was still editing it when she died.

However, my main critique of the Phryne Fisher books is apparent again here. Given its championing of legal and social justice, First Nations people are surprisingly absent from Greenwood’s Bendigo, which sits on Dja Dja Wurrung and Taungurung country, as they were in other books. Her deference to historical policing can also cause modern-day discomfort – the constabulary are always helpful and harmless, with Greenwood not acknowledging the corrupt nature of the behaviour she sometimes portrays. But such misgivings had never made me question if I could read on – until Murder in the Cathedral.

after newsletter promotion

There are plenty of progressive views on feminism, migration, illegitimacy and queerness in this book; Phryne even condemns the false conflation of homosexuality and paedophilia, which “aren’t the same thing at all.” Unfortunately, having rightly separated them, Greenwood then attempts to explain: “Sometimes they get mixed up, because men are so frightened of the idea that they fancy men that their emotions get directed towards children instead.”

This disappointing fumble appears to imply that gay men can accidentally fall into paedophilia and erases straight male perpetrators entirely, which could leave readers to assume that most child sexual abusers are gay men (which is untrue). “What poppycock,” I only wish Phryne had replied, or that Greenwood had struck out the sentence entirely. (It’s not hard to imagine this may have been picked up, if not for the timing of her death.)

In the acknowledgments, Greenwood says she wrote to provide “respite from an increasingly difficult world outside.” For this reader, a single sentence was enough to bring the world crashing back in, which derailed an otherwise enjoyable reunion.