Is Scottish modernism having a moment? After decades of misuse, neglect and demolition, there’s now a flicker of interest in the structures that remain. Earlier this year, the dilapidated studio of textile designer Bernat Klein sold at auction for £279,000 — more than 15 times its guide price. And there’s a hefty new book on the subject to enjoy.

At one time, the country had an embarrassment of modernist riches. After the Second World War, the architectural movement improved the lot of working people. Architects inspired by European modernism transformed schools, churches, hospitals, private villas like Klein’s, even a ski resort. ‘Scotland was to be re-imagined as a modernist utopia,’ writes Bruce Peter in Modernist Scotland, a survey of 150 surviving buildings published this month by The Modernist Society.

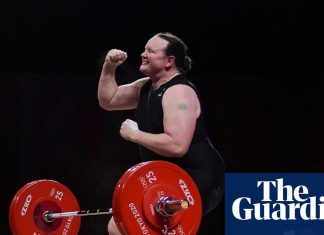

Photography: Bruce Peter.

The Ritz Café in Millport. Photography: Bruce Peter.

The Rothes Colliery Ventilator. Photography: Bruce Peter.

The Northern Cooperative Store in Aberdeen. Photography: Bruce Peter.

Cumbernauld Town Centre Close. Photography: Collection Bruce Peter.

The College of Building and Printing in Glasgow. Photography: Bruce Peter.

By the 1960s ‘new waves of more radical modernism had taken hold, including brutalism coming from Le Corbusier’, says Peter. Modernists who emerged in 1930s Edinburgh — Basil Spence, William Kininmonth, Robert Matthew, Alan Reiach — were part of the cohort who built everything from single-storey, flat-roofed villas in well-heeled postcodes to entire conurbations. Glasgow’s new town Cumbernauld, for instance, was modelled after Nordic modernism.

Klein’s home in High Sunderland, designed by Scotland-based Peter Womersley, was one of the finest buildings, resembling a California Case Study house. Others included RMJM’s Swedish-inspired Queen’s College in Dundee, and a domed cafeteria by Norwegian émigré Jan Magnus Fladmark, near the summit of the Cairngorm ski resort.

As Scotland fell into recession in the late 1970s, publicly owned modernism bore the brunt of decline and unemployment. But while England rekindled its appreciation of the style and listed many brutalist structures, many of Scotland’s succumbed to the wrecking ball. Peter puts the disparity down to lack of awareness. ‘Too many people seem simply not to have been educated to read the environment around them and therefore seem to find it hard to be empathetic,’ he says. ‘At one extreme, it manifests in littering, fly-tipping, dirty camping, but it also appears more generally in a lack of appreciation of buildings of all eras.’ He hopes his book will ‘lead more people to view post-war buildings more positively’.

Klein’s studio is not the only gem to have gotten a second chance. In 2017 Cables Wynd House, the brutalist blocks by Alison & Hutchison & Partners known locally as Banana Flats, won A-listed status and is now being renovated by Collective Architecture.

The biggest hot potato, according to Peter, is Cumbernauld’s town centre. ‘It was thought to be very avant garde in the 1960s, but is very damaged.’ The council wants to flatten it — ‘It’s hard for a non-architect to see what it could become…. If it were partially demolished, leaving the original core, one could have something completely magnificient.’ He likens it to Patrick Hodgkinson’s beloved Brunswick Centre in London, renovated by Levitt Bernstein 20 years ago. If Cumbernauld council doesn’t take the cue and ends up demolishing its own underrated gem, says Peter, ‘people will regret it’.