Hello, dear reader! Do you like what you read here at Omnivorous? Do you like reading fun but insightful takes on all things pop culture? Do you like supporting indie writers? If so, then please consider becoming a subscriber and get the newsletter delivered straight to your inbox. There are a number of paid options, but you can also sign up for free! Every little bit helps. Thanks for reading and now, on with the show!

Given that I grew up in West Virginia, it’ll probably come as no surprise that religion, Christianity to be specific, played a pretty major role in my upbringing. My parents and most of the paternal side of my family were staunch members of the Church of Christ, i.e. the denomination that aims to create a church that is supposedly closer to that of biblical times and thus doesn’t allow instrumental accompaniment during singing (among many other oddities). My maternal side, on the other side, were mostly Methodists, with a few forays into American Baptist. While I largely stopped attending church regularly as a teenager, Christianity was still a major part of everyday life.

As one might imagine, neither side of my family have been thrilled with the revelation–if you can call it that, since I’m not exactly subtle about my queer presentation–that I was gay. And, much though I hate to admit it, neither of my grandmothers ever knew this about me explicitly, though I’m sure they both had their suspicions. I like to think that both Grandma (maternal) and Nan (paternal) would have loved me just as fiercely if they’d known that I was a raging homosexual. They might have been devout, but they weren’t annoying about it, certainly not to the extent that their children have been and, in the case of Grandma in particular, ours was a bond that nothing could break.

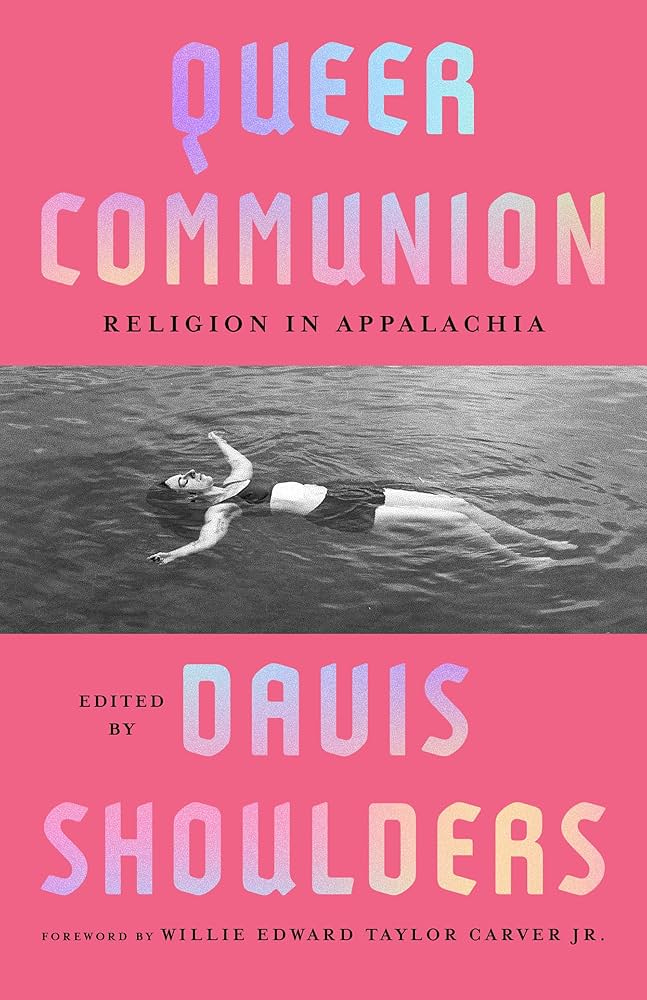

My late grandmothers were much on my mind as I sat down to read Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia, a new collection out this fall from the University Press of Kentucky. Edited by Davis Shoulders, this collection highlights the many complex, complicated, and often fraught ways that queer Appalachians grapple with their faith and their upbringings. Indeed, the first several chapters deal with matriarchs and mamaws, and I had to put the book down at points, so powerful was my emotional reaction. It’s no secret that many queer folks, gay boys in particular, share close bonds with their grandmas and mee-maws and nannies, and that’s true for these writers, too. When I read Savannah Sipple’s essay I felt truly seen, and his part truly stood out to me. “As much as it had hurt to leave home to come out, it hurt more that I’d left Granny, that I hadn’t been able to share this one part of me with her. The one thing. And it felt like the biggest.” Ugh. Even typing those words out has my throat closing with tears.

Thus is the power of faith, of grandmas, of queer love, and of Appalachian bonds.

Indeed, the volume’s wrenching heart is clear from its opening pages, written by Willie Carver, arguably the patron saint of queer Appalachia. The issues that Carver raises–of feeling alienated from the faith in which one was raised but of yearning for some sort of connection; of finding a way back to spirituality by his own path; of standing betwixt and between tradition and something new, run through the book like a deep seam of coal.

As the various chapters in this book make clear, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to queer Appalachians and their faith. Some of those in these pages end up leaving Christianity to pursue other paths, religious traditions that are more fulfilling. Others, like Matthew Jacobson, remain devout, rightly understanding that there doesn’t have to be a contradiction between being a person of faith and being an openly queer person. As he puts it so bluntly and powerfully at the very beginning, “My Catholicism is everything to me.”

While there is joy, there’s pain here, too. How could it be otherwise, when so many of us grew up in faith traditions that made us feel as if we could never be close to God if we lived our authentic lives and embraced queer selves? But, while some essays, like Mack Rogers’ “The father, the son, and the I.D.I. spirit” don’t shy away from the anguish caused by Appalachian religious faith, they also don’t let it define them. Like so many other queers who’ve come from those hills and hollers–and like the ones who still call those places home–they find a way to thrive and to find joy in the sorrow.

Indeed, what may come as a surprise to some is just how joyful this book is. These are writers who have embraced their queer Appalachian religious roots in one way or another, finding solace and happiness and transcendence in the traditions that gave birth to them. In their poetry and their prose, their honesty and their confessions, they show us a way out of the darkness that so often afflicts those of us who grew up in Appalachian Christian traditions.

Two years ago my dad’s eldest sister essentially disowned me as a result of my sexuality. For all that she had told my mom that she didn’t judge others and left that up to God, when it came down to it, when it seemed as if my partner and I might step foot in her house, she made it clear to me in no uncertain terms that neither of us were welcome. While I haven’t been close to my aunt in years, that whole incident left a deep wound on my heart and in my soul that has yet to fully heal. On the whole I’ve been very fortunate that my family hasn’t disowned me, and my parents–both of whom hold their faith in God quite dear, by the way–have always made it clear that both myself and my partners are welcome in their home, that who I am and how I live my life is a matter between me and God.

As I continue to grapple with my Appalachian identity in a long-overdue process of (re)discovery, and as I continue to find my way back to Christianity (though a kinder, more accepting one than the one in which I was raised), I know that Queer Communion will be one of those texts that I return to again and again. There’s a power in these pages that cannot be denied, and there is a strength too. This book is filled with so many beautiful passages that I could spend all day just talking about them, but I’ll close, appropriately enough, with one from Carver’s introduction.

Love, he writes, “is the lens the spirit needs to witness truth lurking behind the brokenness of this world. Love is found in an unwelcoming home, in grandmothers who never knew all the parts of us, in taking back symbols and rediscovering them in new contexts, in art, in dancing with someone, in song, in the present moment, and in growing in ourselves a glorious and expanding truth that cannot be stifled.”

Love can save us and bring us out of despair, and I thank God for Queer Communion and for all of my queer siblings with whom I share this flawed but beautiful heritage we call Appalachian.